“Genocide” evokes crematoria, mountains of skulls, and mass graves. It is what the Nazis did to the Jews of Europe, what the Khmer Rouge did to fellow Cambodians, what Hutu nationalists did to Tutsis in Rwanda. The term, like the practices of death and social destruction to which it refers, is odious. Charging genocide is like ringing an alarm because, when this crime is occurring or when it has occurred, consequences for perpetrators should follow.

Our approach is to trace the political history of the term “genocide” in law and jurisprudence, and compare some of the contexts in which the practices to which the term refers have occurred, and where accountability has been pursued. We also consider where and why there are grey areas in its usage, and offer some thoughts about the political utility and detriments that accompany the charge of genocide.

Arguably, because of the gravity and potential consequences that attach to genocide, deploying it in a manner that does not correspond to its legal definition risks watering down its force, which might further harm those who are victimized by extreme forms of state violence. But we must also ask who is empowered to decide, and what criteria are used to determine whether allegations of genocide are justified. The counterargument could be made that invoking this term to characterize the treatment of Black Americans is perhaps the only way to focus negative attention on the killing of so many unarmed people by police, and to compare it to lynching, which was a direct outgrowth of the enslavement of Black people. Slavery was a genocidal regime both in the expendability of Black lives and in the imposition of social death on the slave. Contemporary mass incarceration results in the physical and social destruction of the lives and communities of people of color, who are disproportionately represented in the US prison population, and provides a new source of unpaid labor, not unlike chattel slavery. In this context, it could be argued, the way to force Americans to consider seriously the disastrousness of ongoing police violence and mass incarceration is to link them directly to the history of the even more brutal violence that begot them. Similarly, the use of the term “genocide” by Palestinians and those struggling against the long-term, systematic and criminal oppression and persecution suffered by Palestinians since 1967 (and indeed, since 1948), is necessary to force a conversation that would otherwise remain very difficult to begin.

We write “it could be argued” because genocide is a term whose meaning and even more so whose applicability remains hotly contested. It can be defined from many perspectives—legal, sociological, political and/or historical, all of which are interrelated yet each of which rests on distinct experiences, assumptions, and criteria of judgment. Determining whether Israel or the United States or indeed any other government can be reasonably accused of genocide depends first on whether the accusation is political or legal in its scope and intentions. To reach a legal standard of genocide, that is, one that accords with the criteria under international law, demands comparison with allegations and judgments of genocide cases that have been heard, tried, and/or judged by international tribunals, such as the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the International Criminal Court (ICC), and various ad hoc tribunals mandated to make such determinations.

But, as we explain below, even the most detailed investigation may not lead to a conclusive determination as to whether specific actions or policies have crossed the threshold because the standards presently used to define genocide remain deliberately vague, and the body of court judgments is limited and recent, dating back less than twenty years. Consequently, we survey existing legal standards and rationalities, and contextualize recent allegations about Israel and the United States in relation to the legal record. Finally, we suggest how violent contexts may be assessed in light of expanding sociological and political deployments of the term.

The Genesis of Genocide

Many wars and conflicts across human history have involved mass violence against whole populations that, today, would unambiguously be described as genocidal. The eighth-century Lushan revolt in China and the Mongol conquest of Eurasia each resulted in what would be the equivalent of hundreds of millions of deaths by contemporary population measurements, dwarfing the scale of the twentieth century`s two world wars combined. Over the last two centuries, civilians have been increasingly targeted for large-scale violence; this can be attributed to many factors, including the build-up of standing armies; technological advances in weaponry that allowed artillery, aerial bombs, and increasingly long-range missiles to reach what previously had been the rear area of enemy territory; and the rise of “totalizing ideologies” that encouraged violence against all members of the enemy`s society. As Alexander Downes has pointed out, in the wars of the twentieth century, “the startling numbers of civilian casualties” and “civilian victimization” more broadly occurred precisely at the very time a consensus emerged that targeting civilians was immoral and should be prohibited. This consensus has taken shape under the rubric of international humanitarian law (IHL), whose origins trace back to the late nineteenth century.

The United States was the first country to attempt to impose a balance between military necessity and humanitarian considerations in the conduct of war. The Lieber Code, produced by Frances Lieber and signed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863, was a set of military orders that took the “best practices” from the laws and customs of war to govern the Union Army during the US Civil War. This Code included the prohibition against deliberate attacks on or other forms of mistreatment of enemy civilians. The Lieber Code served as inspiration for The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, which constituted the first steps in the development of modern international laws of armed conflict, and specified that violations, or “war crimes,” would include deliberate attacks against civilians during international conflicts between states.

However, violations were not abated by these new rules. On the contrary, in the wake of the Ottoman mass murder of over one million Armenians and the similarly devastating (but far less discussed) Allied blockade of the Central Powers during World War I, there was no authoritative determination of war crimes let alone accountability for perpetrators. While these events inspired the development of the category of “crimes against humanity”—a term first used by the Allied powers during World War I to describe the Ottoman massacres of Armenians—and later the category of genocide, they did not obtain any functionality as legal concepts until the Nuremberg Tribunals after World War II.

Raphael Lemkin, a Polish Jewish scholar, coined the term “genocide” in 1943. He had been agitating over the previous few decades for international recognition that what the Ottomans had done to the Armenians should be recognized as egregious and criminal. Originally, what he called the “Crime of Barbarity” (in a 1933 academic paper) included mass murder, but also the “attempt to destroy a nation and obliterate its cultural personality” motivated on the basis of “racial, national or religious considerations.”

But it was the Nazi extermination of Jews and other population groups in Germany and the countries it occupied in Europe that provided the opportunity for Lemkin to push his argument and to name this form of violence “genocide,” which combines the ancient Greek word genos (race, clan) and the Latin suffix cide (killing). In a 1946 article for American Scholar, Lemkin elaborated on the definition of the term, arguing that it involved the “mass obliteration of nationhoods,” the “murder and destruction of millions,” and the “destr[uction] demographically and culturally” of populations within countries. Crucially, Lemkin saw genocide as both an international crime, whose commission was of concern to all nations, not just the one(s) directly affected, and as a crime that could occur during peacetime as well as wartime.

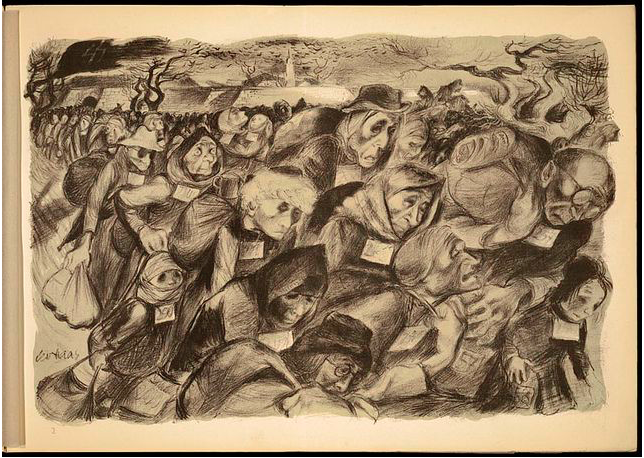

[Lithograph by Leo Haas, who survived Theresienstadt and Auschwitz.]

Not surprisingly, given the background of World War II, Lemkin argued that “genocide can be carried out through acts against individuals, when the ultimate intent is to annihilate the entire group composed of these individuals…Moreover, the criminal intent to kill or destroy all the members of such a group shows premeditation and deliberation and a state of systematic criminality which is only an aggravated circumstance for the punishment.” The objectives of such a plan would be “disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups.” In 1946, the new United Nations General Assembly would declare in Resolution 96(1) that genocide involved “a denial of the right to existence of entire human groups.” (The United Nations was established in 1945.)

Thanks to Lemkin`s passion and labors, that term became a centerpiece in the revolutionary transformation of international law in the aftermath of World War II. Nazis were tried for the newly named and defined crime, and the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, passed by the United Nations in 1948, became the first international human rights law. As enshrined in Articles II and III of the Convention, genocide comprises both a “mental” and a “physical” element, and was defined as the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such.” It would include the commission of acts of killing, causing serious bodily or mental harm, deliberately inflicting on a group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part, imposing measures intended to prevent births, and/or forcibly transferring children outside the victimized group.

According to the Genocide Convention, while the levels of death and destruction do not have to encompass most or even a majority of members of a protected group, the violence does have to be of sufficient intensity and organization to threaten to change its “pattern of life.” In Article III of the Genocide Convention, punishable acts include conspiracy, incitement, and attempts to commit genocide, as well as complicity in these actions, even if they were not successfully carried out. This basic definition has been maintained and reinforced in the ensuing seven decades, including in the Rome Statute of 1998 to establish an International Criminal Court (ICC).

Despite this continuity in the legal definition of genocide since 1948, the term has not remained static. At the time the Convention was being negotiated, experts, including Lemkin, were pushing to include within the definition of the crime an explicit cultural component, which the United States strongly opposed because there was a significant fear that persecuted minoritized groups could pursue genocide claims for the destruction of their culture(s) or forced assimilation into the dominant group`s. Similarly, the definition of protected groups deliberately excluded political groupings or parties, even though—or perhaps because—they were among the most common targets of large-scale state violence.

The Development of International Law

For over a decade after the promulgation of the Genocide Convention in 1948 and the Four Geneva Conventions in 1949, further development of international law was frozen by the Cold War. But with the demise of European colonies and the rise of newly independent nations, a new era of international human rights law-making began. This included the 1960 Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, which condemns “colonialism in all its forms and manifestations” (including illegal settlements established by colonizing populations). The 1965 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination explicitly tied ongoing structural racism to colonialism.

The 1973 International Convention for the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid condemns and makes an international crime against humanity “state-sanctioned discriminatory `inhuman` racism committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them.” The criminal nature of any apartheid regime was confirmed in the 1998 Rome Statute of the ICC. All these laws are considered “peremptory,” meaning every country is legally bound to respect them whether or not they are signatories to the conventions and regardless of their own strategic interests.

The legal application of the crime of genocide has been developed through the work of two ad hoc tribunals established by the United Nations in the 1990s to try suspected war criminals in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, and the creation of the ICC. The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was established in 1993, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in 1994, and the ICC came into being in 2002 when the threshold of signatories to the Rome Statute had been crossed.

The work of these legal institutions in investigating and prosecuting allegations has not been easy, and in fact there has been strong opposition from the start. Many countries have long resisted applying the category of genocide in even the most extreme cases, both because they and their clients and allies have themselves engaged in mass violence that could be so defined, and because doing so in other contexts obligates them immediately to work to stop it, regardless of the military, strategic, or economic implications and difficulties of doing so. The United States in particular opposed labeling the two generative cases of genocide in the post-Cold War era as such; in the case of Bosnia, the Clinton Administration asked government lawyers, in the words of a former State Department lawyer, to “perform legal gymnastics to avoid calling this genocide,” and acted similarly in the midst of the Rwandan genocide lest it “inflame public calls for action.” In contrast, the Bush administration was quick to call the massacres in Darfur genocide, while the Obama Administration was more reluctant to condemn the Sudanese regime.

Despite the fear and opposition of leading global actors, the United Nations at least attempted to hold those responsible for recent genocides to account through the ICTY and ICTR, and later through the ICC. The trials pursued through these venues produced important discussions regarding how best to define genocide. But sadly, none of them brought much clarification to the most ambiguous aspect of the definition in the Convention, namely how extensive does the death and destruction have to be to constitute the partial (“in part”) destruction of a protected group?

[Bosnian Genocide (1995), Forensic experts of the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia inspect remains of the Srebrenica massacre victims in the Pilica mass grave on 24 July 1995.]

A 3 February 2015 ICJ judgement in Croatia v. Serbia is among the most extensive recent attempts by international jurists to provide a more precise definition. In its judgment, the Court asks precisely the question of the “meaning and scope of `destruction` of a group,” the “scale of destruction of the group,” and the “meaning of destruction of the group `in part.’” Croatia argued that “the required intent is not limited to the intent to physically destroy the group, but includes also the intent to stop it from functioning as a unit.” That is, the Convention did not only “imply the physical destruction of the group” but could also include the destruction of the group’s culture. Serbia rejected “this functional approach to the destruction of the group, taking the view that what counts is the intent to destroy the group in a physical sense, even if the acts listed in Article II may sometimes appear to fall short of causing such physical destruction.”

In deciding on this issue, the ICJ noted that while cultural genocide was included in the original draft of the Convention, it was ultimately dropped and thus “it was accordingly decided to limit the scope of the Convention to the physical or biological destruction of the group.” In the Court’s view, this meant that even where a genocidal action “does not directly concern the physical or biological destruction of members of the group, [it] must be regarded as encompassing only acts carried out with the intent of achieving the physical or biological destruction of the group, in whole or in part.”

Biology versus Culture: Lessons from the Native American Experience of Genocide

Of course, in reality, separating the physical or biological from the cultural is impossible. The social construction of the category of race and its inherently political—as opposed to biological—essence put the lie to claims of “permanence” and “stability” of the category. In the sixteenth century, for example, European invaders of the Americas marked the primary difference between themselves and the indigenous peoples by religion, deploying the invidious categories of Christian and “pagan” (or more familiarly “civilized” and “savage”). The biologization of race began in the eighteenth century through the rise of “scientific racism,” used to justify Europeans’ claims to superiority in their imperial and colonial ventures. Scientific racism rules out even the possibility of cultural amelioration because the hierarchy in this system is fixed in nature; it provides an apparently stable (transcendent) rationale for racist and otherwise oppressive policies, including, potentially, genocide. Thus, a “racial” definition is inherently problematic because no clear-cut definition of “the racial” in biological terms exists. (The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination implicitly acknowledges the problematic nature of the term “race” when it describes racial discrimination in broad terms, as meaning “any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin...”)

So, if race is not in fact primarily a biological category, and is clearly inseparable from culture, then “genocide” necessarily should apply to the cultural destruction of a group as well as to its physical destruction. The case of Native America is instructive here. The demographer Russell Thornton estimates the 1492 population of the Americas, north and south, at over seventy-two million. By the twentieth century, the genocidal effects of European colonization had reduced this population to between four and four-and-a-half million. In the United States, in what would become the lower forty-eight states, Thornton’s figures estimate the 1492 population at over five million, reduced to 250,000 by the end of the nineteenth century through war, ethnic cleansing, and biological warfare implemented by the active spread of small pox and the withholding from Native peoples of first the inoculation and then the vaccine (both developed in the eighteenth century). There is little doubt that the level of death and destruction marks the experience of Native Americans as one of genocide, but it has never been officially labeled as such, nor are the United States or other governments in the Americas going to acknowledge such a designation in the near future, given the profound ethical, political, and perhaps even legal ramifications of such an admission.

All of these hemispheric Native American communities defined themselves culturally; their languages and worldviews did not contain a nature/culture opposition. Indeed, there is no category of “nature” as distinct or separate from the cultural or social world. In the United States, it was not until the mid-nineteenth century, with the 1846 case of United States v Rogers, that the term “Indian” was racialized to place white men adopted into tribes, and thereby subject to tribal law, under federal US jurisdiction. In the same vein, at the end of the nineteenth century, the US government imposed a blood-quantum regime on the Native nations in the lower forty-eight states in order to diminish the number of Indians further. The nations themselves adopted this regime in the 1930s following the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. The idea of blood-quantum was always a bureaucratic fiction because the requirements for tribal membership vary radically from tribe to tribe, thus revealing the cultural and political basis of what is legally considered a racial identity. Indeed, in the 1974 Morton v Mancari decision, the Supreme Court seemingly reversed the previous stance by declaring that Indian hiring preferences in the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) did not constitute racial discrimination because the term Indian under certain conditions referenced a political, not a biological, group. Both cases stand as precedent in US jurisprudence.

[Massacre at Wounded Knee, December 1890.]

Since the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890, the continued genocide of Indians in the United States has been accomplished by means other than physical obliteration. This includes, for example, forced assimilation through the boarding-school system (taking Native children from their natal families) that lasted from the late nineteenth through the mid-twentieth century, the forced sterilization of Native women in the 1970s, the transfer of Native children to non-Native families (partially brought to an end in 1978 with the passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act), denial of federal recognition for tribes, and the dis-enrolling of tribal members from the rosters by members of their own tribes. In this latter case, as Frantz Fanon has taught us, the colonized do the work of the colonizers.

The relevant question here is: at what point does the destruction of a culture that constitutes a group’s identity (e.g., traditional values such as language and patterns of interaction with members of the group through the bonds of extended kinship) amount to (an actual or attempted) genocide? Simply put, can genocide be committed without the physical destruction of the group or even part of the group, even though historically physical destruction paved the way for cultural destruction? At least for the present, the exclusion of culture as a recognized category in interpretations of the Genocide Convention precludes it from being part of a legal determination of genocide. In the same manner, political groups or affiliations (such as membership in a particular party or movement) were excluded because of pressure from governments that feared their own persecution of dissident parties could then fall under the genocide rubric. This was justified by the aim of focusing the definition of the crime on more “stable” and “permanent” groups which people could not join or leave “at will.”

We explore the possibilities and implications of expanding the legal definition of genocide and the role of non-legal (i.e., sociological and political) definitions and debates in that process at the conclusion of this essay. For now, let us return to the existing legal regime encompassing the term, where the scale of physical/biological destruction of a group or members remains of paramount importance.

The “Scale” of Genocide

On the question of the “scale of destruction” of the victimized group, in Croatia v. Serbia the ICJ considered that “in the absence of direct proof, there must be evidence of acts on a scale that establishes an intent not only to target certain individuals because of their membership in a particular group, but also to destroy the group itself in whole or in part.” As for just how great a part of the group must be affected before such actions can be considered to have met the criteria for genocide (rather than being “merely” a crime against humanity), the ICJ recalled its own 2007 opinion on the applicability of the Genocide Convention to the Serbian war on Bosnia, and noted that “it is widely accepted that genocide may be found to have been committed where the intent is to destroy the group within a geographically limited area... [I]f a specific part of the group is emblematic [that is, representative] of the overall group, or is essential to its survival, that may support a finding that the part qualifies as substantial within the meaning of [the law].”

The problem here is how one is to determine whether a part of the group under consideration is “emblematic.” During the more than century-long Navajo-Hopi land dispute, for example, approximately twelve to fourteen thousand Navajos were forcibly removed from their ancestral homes in what had become, by court order, Hopi Land. The effects of this removal were devastating in psychological, social, and cultural terms to these people as land in Native cultures is considered part of the kinship nexus, a living entity. Among these Navajo families, of which only a few remain on what is termed the Hopi Partitioned Lands, are some of the most traditional Navajos, who are repositories of the historical culture, including, of course, the land from which they were removed; traditionally, Navajos bury the umbilical cords of their children on their land and when a Navajo dies, he or she is meant to be buried with his or her cord.

Do we, then, consider this “part” of the population of over three hundred thousand Navajos “emblematic”? And what are the effects of this removal on Navajo culture? These questions, which are not rhetorical, were not considered by the courts which sanctioned ethnically cleansing this area; instead, they focused on the limited set of questions surrounding land rights. Moreover, as we discuss below, “ethnic cleansing” is not at present legally a part of the juridical definition of genocide.

What the Navajo-Hopi experience tells us, however, is that while there may well be good reason for the legal definition of genocide to maintain a demographic “floor” below which actions (as opposed to intention or incitement) are not considered to meet the threshold, basing the legal determination of genocide largely on such a calculus is quite problematic. Nevertheless, it remains that the ICJ`s 2015 judgment, like its 2007 decision, and decisions by the ICTY, ICTR, ICC and other UN investigations such as those examining potential genocides in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Darfur, all tend to cohere towards an understanding that for a specific action to be considered an act of genocide, it must involve “physical or biological destruction” to such an extent that the continued functioning and even survival of the larger group is “conclusively” and “convincingly” threatened. We can imagine that ongoing or recently completed cases in the Sudan, Uganda, the Central African Republic, Kenya, and the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire will further explicate the legal parameters for genocide prosecutions.

Indeed, as the ICTY and ICTR have determined, when direct “smoking gun” documentary evidence (e.g., protocols of meetings, private or public statements or plans that lay out a specific plan) of genocidal intent is absent, it is precisely the “scale of atrocities committed” and the clear intent by perpetrators to “destroy at least a substantial part of the protected group” that is the determining factor. As the ICJ concluded its 2015 judgement in Croatia v. Serbia, “Genocide presupposes the intent to destroy a group as such, and not to inflict damage upon it or to remove it from a territory, irrespective of how such actions might be characterized in law.”

Applying the Genocide Calculus to the History of Palestine and Israel

Now that we have an understanding of the ambiguous parameters surrounding the legal determination of genocide, we can look at the actions that Israel has engaged in during its half-century occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, and even further back to the war of 1948, in order try to consider whether they constitute in whole or in part the crime of genocide. Let us begin with the 1948 War, which included dozens of incidents involving the deliberate killing of significant numbers of civilians and several massacres involving dozens and even hundreds of dead.

Martin Shaw proposes a broad interpretation of genocide, with specific reference to the 1948 War and the Palestinian Nakba: “Genocidal action aims not just to contain, control, or subordinate a population, but to shatter and break up its social existence. Thus genocide is defined, not by a particular form of violence, but by general and pervasive violence...” We would suggest that Shaw’s interpretation raises some questions. What is the line, for example, between containment and shattering? When does containment amount to a shattering of a group’s social existence?

There is also the question of determining when violence becomes “general and pervasive” as opposed to “limited,” particularly when that judgment depends, first, on defining whose death is a targeted objective and whose is “collateral.” In instances of smaller scale killing, such as “partial massacres,” according to the narrow (physical and biological) criteria used by the various tribunals charged with adjudicating claims of genocide, there must be evidence of intent towards mass murder and social destruction in order to constitute genocide; the extent or scope of a particular act of violence must be clearly intended to achieve the goal—even if unrealized—of the physical destruction of the larger group.

The critical term here is “intent.” By what criteria is perpetrators’ intent to be determined, and can intent to commit genocide be expanded to include knowledge that certain deliberate actions are likely to lead to genocide even if that is not the specifically stated intention? This is another area where jurisprudence and sociology (and scholarship more broadly) can produce differing determinations about the standards and thresholds for genocide.

In Shaw`s view, Zionist/Israeli actions during the 1948 War, both in terms of the broader ethnic cleansing of Palestine and in the context of the multiple massacres of civilians, reveal an “incipiently genocidal mentality” that reflected the “settler colonial” and “exclusivist nationalis[t]” character of Zionist and then Israeli identity, ideologies, and policies. The combination of underlying intentions and ideology with the acts of exceptional violence against civilian populations (especially the mass killings and/or destruction of more or less entire villages epitomized by the Deir Yassin massacre and the battle for Lydda), the deprivation of Palestinians` fundamental right of self-determination, the dispersal of the majority of the population, and the destruction of almost every national institution, taken together arguably could be described as genocidal. On the other hand, however, the deliberate exclusion of ethnic cleansing from the Genocide Convention, even as populations across the globe (most notably, in the partition of India and Pakistan) were being “cleansed” from their homes to create more homogeneous territories, was a deliberate and very significant fundamental lacuna in the coverage provided by the Genocide Convention.

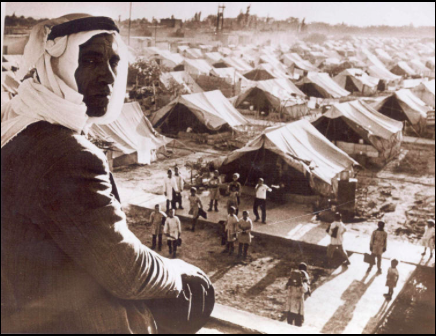

[Palestinian Nakba 1948, Jaramana Refugee Camp, Damascus, Syria. Source: Wikipedia. ]

However important the 1948 War and Palestinian Nakba are historically, the contemporary claims that Israel has committed genocide against Palestinians are focused primarily on its ongoing occupation of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip.

Numerous reports and assessments by leading local and international human rights organizations (including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, B`Tselem, Adalah, the Palestine Center for Human Rights, al-Haq, Peace Now`s Settlement Watch, Defense of Children International), as well as by the United Nations, and the US State Department provide strong evidence and compelling arguments that Israel has committed innumerable war crimes and crimes against humanity. Israel frequently violates even the broadest interpretations of the principles of distinction (distinguishing between legitimate military targets and protected civilians and non-combatants) and proportionality (limiting the use of force to the extent necessary to achieve legitimate military objectives).

The list of well-documented crimes include indiscriminate, willful, and lethal attacks on civilians, inhumane treatment, collective punishment, deprivation of the right to a fair trial, closing off of entire regions and confinement of civilians within them, the use of human shields, home demolitions, illegal and arbitrary detention, torture, imprisonment of children, rape, looting, destruction of infrastructure, extrajudicial killings, deportation and exile of members of the occupied population, refusing to allow protected persons to return to their homes after hostilities, as well as the establishment of non-military settlements and the movement of Israel’s own Jewish citizens into these occupied areas. Apart from Israel’s actions during active hostilities, the daily functioning of the occupation and its goals and objectives are inherently unlawful as they continuously and without respite involve illegal expropriations of land, theft and destruction of crops and natural resources, theft and deliberately polluting and poisoning of water supplies, and impeding and even prohibiting the development of the occupied economy.

What Israeli geographer Jeff Halper has described as the government`s “matrix of control” over the occupied territories has involved a level of near total control over Palestinian movement, economic, and political development to the point where Israel violates almost every one of its obligations as the internationally recognized occupying power. Israel`s actions in the occupied territories are characterized, as the ICJ has described it, by “impunity across the board.” These actions and the policies on which they are based clearly meet the standard for such international crimes as persecution, colonialism, racial discrimination, and even apartheid.

Israeli Officials’ Position on the Destruction of Palestine

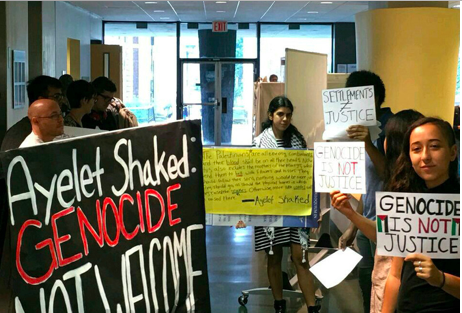

In recent years, several Israeli officials and leading media outlets have suggested the state’s “right” to eradicate Palestinians, and have called for large-scale murder and even genocide of Palestinians. For example, the Chief Army Rabbi, Eyal Qarim, has explicitly advocated the rape of “gentile women”—in this case Palestinians, while the current Justice Minister, Ayelet Shaked, declared that “the entire Palestinian people is the enemy” and called for its destruction, “including its elderly and its women, its cities and its villages, its property and its infrastructure.” As should be clear from the discussion above, Shaked’s statement is an unambiguous call for genocide, and similar calls are being made by senior Israeli officials who directly shape the policies of the government and influence attitudes of soldiers towards Palestinians.

[Students protested Ayelet Shaked during an event at Columbia Law School, 19 September 2016. Source: Columbia University Students for Justice in Palestine.]

Although the standards and consequences of incitement in international case law remain underdeveloped, the United States Holocaust Museum declares that “public incitement to genocide can be prosecuted even if genocide is never perpetrated.” The power of this language regarding incitement could be mobilized in regard to ubiquitous calls for “death to Arabs” or certain officials’ stated desire to turn Gaza into “a graveyard.” With each passing year, accusations of incitement to commit genocide are becoming increasingly plausible, especially when linked to large-scale crimes that have been committed in the assaults on Gaza over the last decade.

Despite the heinousness of Israel’s actions in the occupied territories, under the current legal interpretations of genocide, it would be practically impossible to prosecute any Israeli leaders or state-sponsored individuals for this crime. Quite simply, the number of people killed and their percentage in the larger Palestinian population in the historic homeland or in diaspora do not rise to the levels that have occurred in conflicts where genocide prosecutions have taken place, given that current interpretations and enforcement proceedings hinge on the issue of “scale.”

If we focus on the most recent conflicts, in Gaza in 2008-09 and 2014, the numbers of civilian deaths are approximately nine hundred in 2008-09 and fifteen hundred in 2014. Another one hundred-plus civilians were killed during the briefer but still intense 2012 conflict. All told, the number of Palestinians killed by Israel during the last fifty years constitutes less than one percent of the worldwide Palestinian population today.

These numbers are horrific and unjustifiable by any legitimate military or strategic logic based on the criteria of distinction and proportionality or the laws of belligerent occupation, which limits the use of force by an occupying power to policing and prohibits the kinds of heavy weapons and indiscriminate attacks favored by Israel. (We do not discuss Israeli casualties and deaths or the use of terrorism by Palestinians here, both because no serious argument has been or can be made that they constitute an attempt or even incitement to genocide and because the intent and scope of Palestinian violence against Israelis does not excuse or mitigate Israeli violations of international law and are thus irrelevant to this discussion.) The question before us is whether, in the context of the evolving legal and jurisprudential history of genocide described above, the level of violence against Palestinians, both the numbers of dead and the far greater numbers of wounded, imprisoned, pushed from their lands and otherwise suffering from Israeli war crimes, crimes against humanity, apartheid, and the everyday structural violence of a half century of occupation, rises to the level of genocide as defined in international law.

Many critics of Israeli state violence, including some Israeli and non-Israeli Jews and even Vatican officials, have in fact compared the situation in Gaza to the plight of Jews in Nazi concentration camps or the Warsaw Ghetto. Statistically the comparison does not hold; ninety-eight percent of Warsaw`s Jews ultimately perished, while sixty-three percent of Europe`s pre-war Jewish population were killed during the Holocaust, compared with .5 Gazans and .2 percent total Palestinians killed since Israel withdrew its soldiers and settlers from Gaza in 2005. In comparison, upwards of eight hundred thousand Rwandan Tutsis (seventy-five percent of the population) were murdered during the hundred days of genocide in 1994, while over two hundred thousand Bosnian Muslims (ten percent of the pre-war Muslim population) were killed by Serbs between 1993 and 1995.

If we move beyond the number of Palestinians killed by Israel to other aspects of life under occupation, including the siege of Gaza since 2005 (which is an illegal form of collective punishment and a crime against humanity), the occupation clearly has taken a high toll on Palestinian economic, social, and political development, including devastating effects related to the most basic human development levels such as malnutrition and food insecurity (which reached chronic levels, as the World Health Organization, Red Cross, and other relief organizations have documented). Harvard University scholar Sara Roy aptly has described the overall trend as far beyond mere frustrated or stunted development, reaching rather a condition she terms “de-development,” meaning that Israel has actively pushed back the trajectory of development within Palestinian society.

Yet despite more than a half-century of occupation, Palestinian society remains surprisingly vibrant and resilient, a “lower middle income” country whose gross levels of human development have increased significantly in the last four decades—certainly not as much as if Palestine had been an independent country, but greater than other Arab countries like Egypt or Syria (before the war). We do not argue that these figures somehow indicate a beneficent Israeli rule. Far from it; there are numerous reasons why Palestinian human development levels have increased that have nothing to do with Israeli policies, including remittances from family members working abroad and highly distortive levels of foreign aid. Moreover, the conditions of life in Palestinian refugee camps, particularly outside historical Palestine, remain far more severe than those within the occupied territories.

The question could be raised as to how the present levels of Palestinian human development would be understood in reference to a claim of incitement, conspiracy, or intent to commit genocide. We believe that Israeli officials would argue that, given their ability to inflict far greater damage on Gaza, the situation demonstrates a lack of intent to commit genocide under the current legal definition. Indeed, they have repeatedly and successfully argued that their use of force was comparatively measured by utilizing such indicators. Similarly, the desire of Israeli leaders to “keep Gaza`s economy on the brink of collapse” (cited in documents released by WikiLeaks quoting Israeli diplomats) indicates the intent to commit crimes against humanity, since doing so would involve repeated violations of Article 147 of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

[Six months after Israel’s August 2014 war on Gaza, 19,000 destroyed homes had not been rebuilt and 100,000 people were still homeless, many are living in makeshift camps or schools. Source: Days of Palestine.]

What might we conclude if we looked at the totality of the occupation in terms of the legal definitions of genocide? Could we argue, following Israeli historian Ilan Pappé, that the full measure of Israel`s actions over half a century constitutes what he has termed an “incremental genocide”? Under the present legal understanding of genocide, the answer is most likely no, not least because no such temporal categorization has ever been recognized by the relevant courts. But Pappé is not the only one to deploy such a concept. In West Papua, Indonesia, Indigenous Papuans’ lives have been brutally disrupted by one of the world`s biggest mining operations. Researchers and advocates have warned that the community is suffering a “slow motion genocide” as the mines destroy their habitat and way of life. This is compounded by the government’s systematic discrimination and treatment of them as an “enemy,” and the increasing presence of non-Papuan Indonesians who have made them a minority in their own territories.

The West Papuan dynamics are not that different from those in other settler colonial settings such as Australia or Israel/Palestine. Analyzing the situation in Papua, genocide scholar Kjell Anderson argues for “developing a new analytical model" to delineate different degrees and timeframes of genocide. Specifically, Anderson distinguishes “high-intensity ‘hot’ genocides” epitomized by the Holocaust, and what he calls “atypical,” “cold,” or “slow motion genocides.” These do not involve mass murder, but rather occur “incrementally, over years, or even generations.” Crucially, Anderson argues,

Colonial or neo-colonial genocides targeting indigenous peoples often occur in such a manner. In these cases the physical destruction of the indigenous people may not be directly intended; rather, the perpetrators substantially undermine the foundations of existence for indigenous groups through systemic oppression or willfully reckless policies. These policies are often rooted in dehumanising constructions of indigeneity whereby indigenous people are said to be primitive obstacles to the progress of civilization and the collective interests of the legitimate political community.

Would Israel`s treatment of Palestinians fit Anderson`s criteria for slow motion or cold genocide? On the one hand, his model is certainly closer to the situation on the ground than the traditional legal definition of genocide with its focus on the extent of intended or actual death and communal disintegration. On the other hand, even the most incremental or slow-motion attempt to “destroy” the Palestinian population would, after this much time, have taken a far higher toll on the population than has in fact has happened, or which has been suffered by the inhabitants of Western Papua. The issue of “scale” remains paramount to the legal calculus.

For these reasons, we feel it is important to raise awareness about the expanding scholarly understanding of genocide precisely because such discussions can and should ultimately lead to similar discussions in the relevant international tribunals. The idea of establishing a scale of genocidal behavior (not to be confused with incitement, conspiracy, or intent to commit genocide) that would include the experiences of groups such as West Papuans and Palestinians, and in the process also reintegrate concepts like cultural and political genocide (originally termed “politicide”) into the matrix of legal meanings is worthy of study by scholars and advocates. Such an approach would seem to make room for the concepts of incipient (Shaw), incremental (Pappé), or slow motion (Anderson) genocides discussed here to become part of the legal discussion as the term evolves.

However, in the current legal environment, we believe it would be very difficult to prove that the Israeli government has intended or conspired to commit genocide during the occupation (whether incremental or concentrated). (Others have reached the opposite conclusion, including, most recently, an analysis published by the Center for Constitutional Rights titled “The Genocide of the Palestinian People: An International Law and Human Rights Perspective.”)

Incitement, however, is another matter. We believe that there is evidence of incitement to genocide by Israeli leaders, which should be addressed immediately at the international level. Their language is consistent with cases dating back to Nuremberg where political leaders have been prosecuted for incitement. Incitement is particularly important because it is an “inchoate” crime under international criminal law; that is, its underlying intended crime “need not actually occur for the crime to be proven,” and because it is one area of genocide law where there has been an evolution in the legal understanding and definitions of the concept, both in international and in domestic laws.

The Poetics of Genocide: From Legal to Sociological and Political Understandings

In our view, a “poetics of genocide” would invite the study and comprehension crucial to expanding its legal and other understandings. A poetics tries to establish the definitional limits of a given term (as Aristotle did with the term tragedy in his Poetics). Thus, a poetics is called for when the limits of a term are by no means clear. We contend that the need for such a poetics is pressing because, in recent years, the term genocide is being used to describe situations where its use has provoked confusion and opposition.

If Palestinians have not in the last fifty years experienced genocide as defined in international case law and interpreted by adjudicating tribunals, this does not suggest that they have not suffered egregiously under Israeli occupation. In fact, as we detailed above, Israel has routinely and systematically committed war crimes and crimes against humanity. The extent of Israel`s crimes are such that individual state agents, in principle, could be prosecuted for the international crimes of persecution, colonialism, and apartheid. Any pursuit of these allegations would profoundly alter the international position of Israel, which could be subject to sanctions and other harsh measures until it stopped perpetrating these crimes. As signatories to the conventions that define these crimes, Israel`s foreign-government supporters, including the United States and the states of Europe, would be extremely hard-pressed to avoid punishing Israel in some meaningful form in the wake of such a judgment.

Given that increasing numbers of Americans and Europeans are now willing to consider Israeli culpability for crimes against humanity and apartheid, we would urge that strong and concerted efforts be made to build both the legal and the public case for such prosecutions. We also believe that in this context, a focus on accusing Israel of genocide as a legal matter remains strategically counter-productive, since it would drain energy away from the intensive work necessary to gain a decision on these other serious international crimes, might unify skeptics and adversaries around a position that Palestinians exaggerate their suffering, and alienate sectors of the public and political audiences whose support would be needed to force the politically cautious tribunals to consider them.

We thus suggest a focus on pursuing complaints that are more likely to be adjudicated. But we also support a second and simultaneous process to engage in the more long-term work of changing the accepted legal definition of genocide to include actions that do not meet the current standard. It may be the case that genocide has both sociological and legal definitions and meanings. But we are not talking about sociological arguments here; the Israeli occupation is, first and foremost, a legal regime. If it is going to be challenged and ultimately defeated, it will be on the basis of law far more than sociology. But at the same time, we need to consider how the legal term can evolve—first through its development within sociological, political, and legal theory, and then through the gradual application of newer interpretations and concepts by the ICC and other judicial bodies in actual cases.

Whenever one is discussing the force of law, the question of interpretation and the authority to determine the meaning of language (the language of the law in this case) is critical. The hierarchies of legal authority are inherently colonial—and this is true even in contemporary “post-colonial” contexts. When we discuss the problem of interpretation, we must address the problem of translation. The primal crime of US federal Indian law, for example, was/is to translate Native relations to land, in which land is conceived as non-fungible because it is literally part of extended kinship systems, into property relations, which the legal scholar Robert Williams has called the legal rationalization for genocide.

Taking an example from another context, in current Bolivian and Ecuadorian law over which Indigenous peoples in both countries have had a significant influence, the land (pachahmama, or mother earth) is accorded human rights. To kill the land (and from an Indigenous perspective one way of killing it is to turn it into property), then, is to commit genocide. One of the charges articulated by the Native resisters to the Dakota Access Pipeline (based in the US state of North Dakota) is “environmental genocide.” The question is, then, who makes the law and who gets to interpret it? What do its terms include and exclude? Who is inside the law and who is outside and by what definitions are the inside and the outside constructed and how do understandings and definitions in one context impact those in another?

As we argued above, cultural genocide and ethnic cleansing are two categories of destruction that could have been included in the parameters of the Genocide Convention, but were not because of political considerations. Indeed, in a recent debate between Benny Morris and Daniel Blatman about ethnic cleansing in 1948, published in Ha’aretz, Morris argues that people who do not leave directly under fire should not be considered ethnically cleansed even if they are not allowed to return to their homes after the conflict. This argument provides a negative illustration of the importance of providing a firmer legal foundation for considering ethnic cleansing an international crime and determining its relationship to genocide.

The definitional and interpretative limitation of genocide to physical/biological destruction to the exclusion of cultural or political dissolution was done in part to prevent colonized peoples from bringing successful claims of genocide against their colonizers. Lemkin himself was guilty of such sentiment, as he opposed adding colonialism to the list of crimes precisely because it could lead to such charges being made against the very European powers without whose strong support the Genocide Convention would have had no chance of adoption or ratification by the United Nations and its member states. As William Schabas explains in the introduction to his generative Genocide in International Law, “For decades, the Genocide Convention has been asked to bear a burden for which it was never intended, essentially because of the relatively underdeveloped state of international law dealing with accountability for human rights violations...This has changed in recent years.”

In other words, as the international legal and political environment changes, there is room for the legal understanding and meaning of genocide to evolve further. But for this to occur, legal scholars need to spend a lot more effort creating the legal—and as important, the political and moral—foundations for such an evolution.

In this context, it is worth reiterating that there has been little expansion of the legal definition of genocide since 1948, but sociologically speaking, the concept has been greatly expanded. Concepts such as “politicide” or “ethnocide,” which were explicitly left out of the Convention by its drafters, have gained increasing acceptance among scholars, policymakers, and some sectors of the public. We consider politicide to be an especially useful term because it was included in the original draft of the Genocide Convention, but left out of the final version, both because of fears that repressed political groups and parties might use it to bring charges against their governments, and because membership in such groups was not thought to have the requisite “stability” to require protection by the Convention.

Israeli sociologist Baruch Kimmerling used the concept politicide, rather than genocide, to describe Israel`s clear aim and successful execution of long-term policies geared to “the dissolution of the Palestinian people’s existence as a legitimate social, political and economic entity” by preventing any possibility of Palestinians achieving sovereignty and independence in their own nation-state.

To engage in a poetics, we might ask then, what are the limits of genocide? When does it begin and end? Lest we imagine that the past does not pre-determine the future, the present-day suffering under a continuing US colonialism and resistance to it of so many Native American communities reminds us that the crimes of previous centuries can directly impact the injustices of the present if they are not squarely faced and addressed. Palestinians can be expected to obtain no more justice than Native Americans if Israel retains the same level of power and impunity for the foreseeable future and no reckoning with its past is forced upon it.

Conclusion: Expanding Terminology

The mechanisms through which the decimation of Native Americans proceeded and their oppression continues to raise the question: Can genocide be committed without the physical destruction of the group or even part of the group, even though historically physical destruction has implemented cultural destruction? The answer seems to be “yes,” but this is a sociological answer as of now, without any legal implications unless and until one of the relevant judicial bodies uses these facts to help reshape the legal definition of genocide.

In order to make it possible for the crime of genocide to be discussed and alleged in the context of either historical or present-day situations—whether in occupied Palestine or urban America where present conditions do not meet the current legal definition, jurists and scholars must expand the conceptualization of genocide regarding which groups are protected and what actions are covered in the Genocide Convention. It is worth noting that Palestinians already constitute a protected (“national”) group, which is covered under the Convention. Similarly, it is important to expand the scope of criminal culpability beyond the requirement for evidence that perpetrators specifically intend to commit genocide to a “knowledge-based approach” that would extend criminal culpability to include awareness of the likely implications of specific actions. However, such a change would not affect the evaluation in this case without a change in the type and scope of actions covered by the Convention.

On the other hand, especially in light of increasingly open and public comments by Israeli officials who have called for rape, mass murder, destruction, and other international crimes against Palestinians, we reiterate that accusations of incitement to commit genocide are becoming increasingly plausible, especially when linked to large-scale crimes involved in the assaults on Gaza over the past decade. At the very least, as the ongoing impact of the 2004 ICJ Advisory Opinion on the West Bank “wall” demonstrates, if a mandated UN body such as the General Assembly (which requested the 2004 opinion) could be convinced to request an ICJ opinion, the resulting investigation into all the issues raised in this essay would go a long way towards clarifying the international judicial understanding of Israel`s conduct as the occupation passes the half century mark.

This action is separate, however, from the broader question we have attempted to address in this essay: whether it is possible and advisable to expand the definition of genocide to cover actions that are today not considered sufficient to warrant the application of the term in a court of law. The above discussion of the situation facing Native Americans, as well as the ongoing state victimization of Black Americans as highlighted by the Movement for Black Lives (which in fact caused an uproar last year when it`s manifesto included language accusing Israel of genocide), suggests reasons for so doing. And indeed, in recent years, countries such as France and Romania have seen an expansion of genocide in case law.

Simply put, change can happen, albeit often quite slowly. We stress here that we are not advocating “lowering the bar” or standard for genocide so that acts which clearly do not involve the intent, policy, or actual physical destruction or disaggregation of communities are covered. Rather, we are calling for a broader consideration of what kinds of actions meet the existing standard.

In the case of Israeli actions against Palestinians, a two-fold strategy would seem to be called for: First, educate the public about the extent and severity of Israeli crimes and the applicability of existing international conventions and laws, such as those against apartheid, racial discrimination, persecution, and crimes against humanity. Israel`s routine and long-term violation of these laws already carries profound legal consequences should they be applied. Second, call for an expansion of the legal definition of genocide to allow crimes involving ethnic cleansing and the mass killing of presently unprotected groups (i.e., those based on culture or political affiliation), as well as politicide, to become part of the legal epistemology and jurisprudence surrounding genocide.

Ultimately, broadening the sociological understandings and through them legal definitions of genocide will play an important role in the struggles to compel Israel, the United States, and far too many other governments to end their long-term, systematic oppression of brutalized populations and behave in compliance with international law. But before that can occur, a lot more groundwork needs to be done, and activists and academics should consider the political and strategic costs of accusing governments of genocide before the legal and political environment exists for such an accusation to bear fruit.